The UK is to trial a four-day week. But is it practical? How can companies afford it? Would a four-day week mean lower wages?

"Yesterday, I worked two full hours!" said George Jetson, who was moaning about his boss, Mr Spacely.

"Well, what does Spacely think he's running? A sweatshop?" replied George's wife, Jane.

The Jetsons was set in the year 2062. It's a funny thing, but technology critics often cite the Jetsons with its flying cars and ten-hour working weeks to illustrate why reality has not fulfilled the dreams of the technologists. But then we are still 40 years away from the Jetson's time. So they are being a tad hasty.

Besides, the Jetson's was a comedy. No one seriously believes that a two hour day will ever be realistic. But how about a four day week, or a 32 hour week? Or maybe just more time off for holidays?

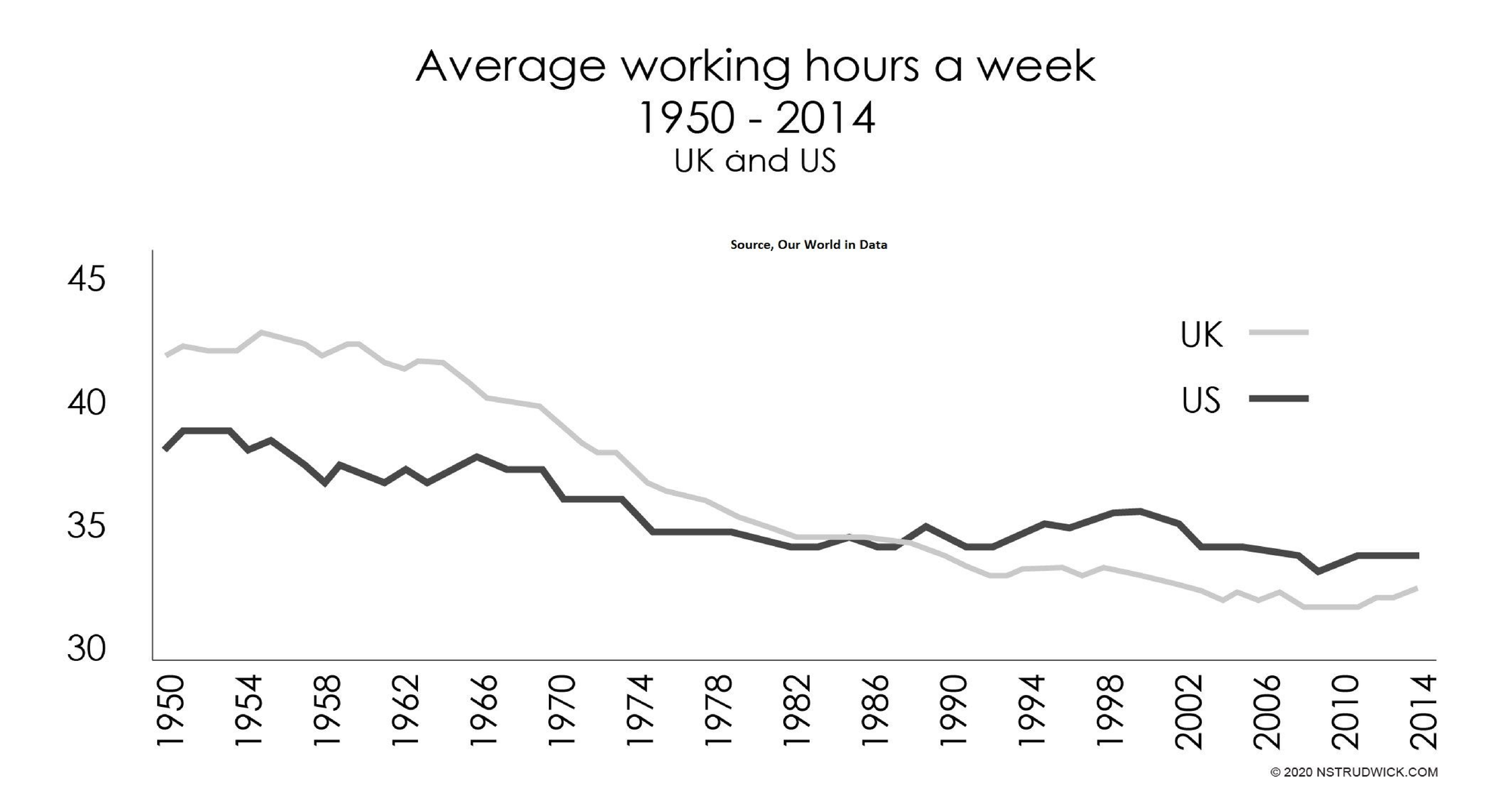

History tells an ambiguous story.

Quoting from Living in the Age of the Jerk, written by Michael Baxter.

Back in the Middle Ages we typically worked a few hours. As Juliet B. Schor writes: "All told, holiday leisure time in medieval England took up probably about one-third of the year. And the English were apparently working harder than their neighbours. The Ancien Règime in France is reported to have guaranteed fifty-two Sundays, ninety rest days, and thirty-eight holidays. In Spain, travellers noted that holidays totalled five months per year.(Science Daily, Farmers have less leisure time than hunter-gatherers, Pre-industrial workers had a shorter workweek than today's from The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure, by Juliet B. Schor.)

In Europe, it changed with the industrial revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. By 1800, the average farm labourer worked 8.2 hours a day. One hundred years ago, the average working week in Belgium was just over 70 hours.

There is good news, however. In the twentieth century, things got better. Today, the average working week in Belgium is 35 hours; in short, the working week in Belgium has halved in 150 years. It is a similar story in Switzerland, Italy and France.

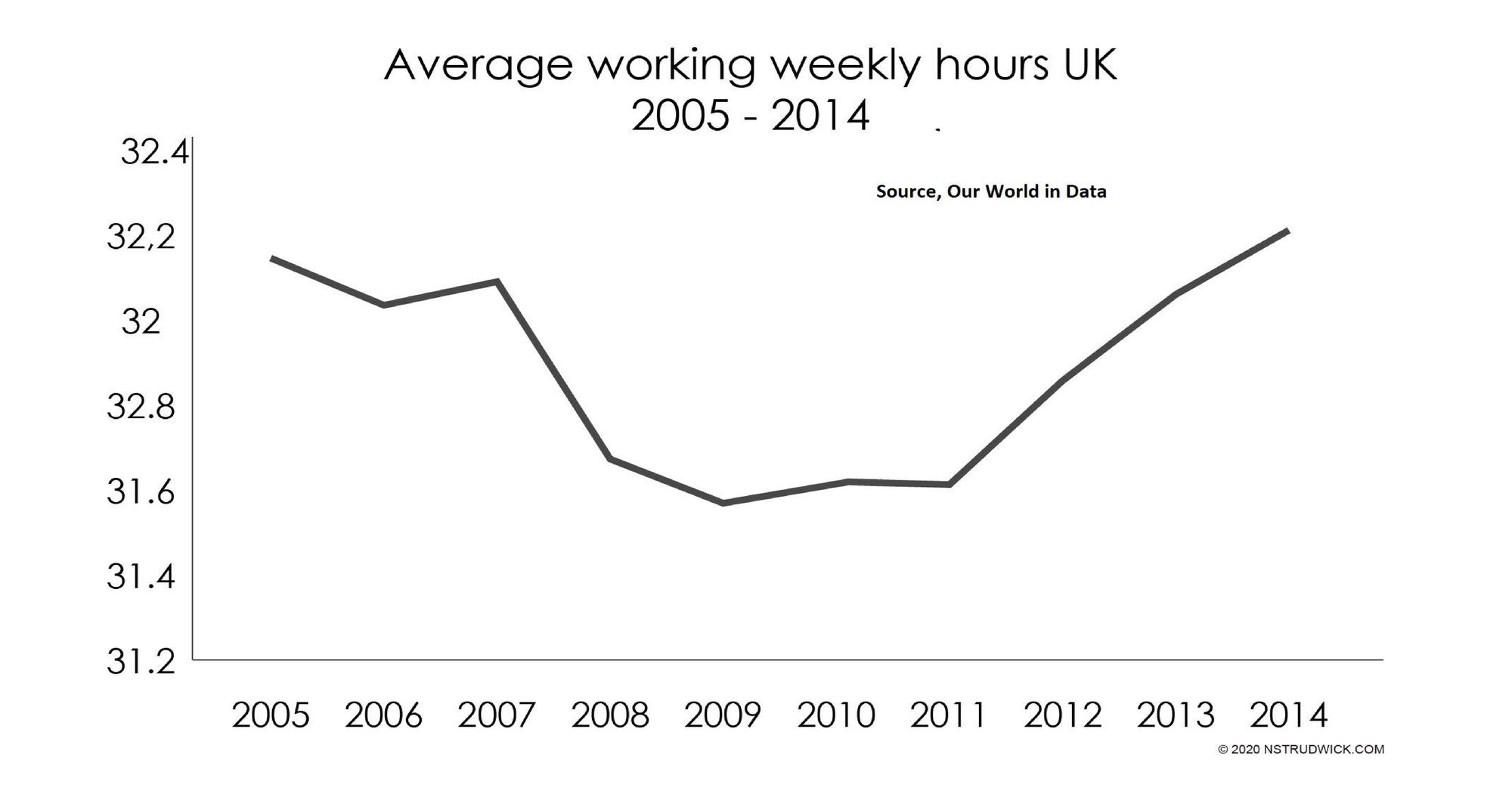

In the UK, the average length of the working week fell from around thirty-three hours in 1992 to about thirty-one and half hours in 2005. But with the financial crisis of 2008, things went into reverse. By 2016, the average working week was back to thirty-two hours.

And now, the dream of a four-day week is on the agenda.

In the UK, 30 companies are taking part in a trial to test a four-hour week.

But not everyone likes the idea. Arguments against the four day-week typically fall into two camps.

There is the how can companies possibly afford a four day-week argument? And then there is the practicality of the idea. We spoke to two experts and asked them to respond to some of the doubts concerning a four-day week.

How can company's afford a four day week?

Damien Stork, mental health thought leader and founder of CHX Performance

"I think the point of the 4-day week is as much about productivity as it is mental health. Restoration is critical in high performance, and it follows that putting in place restorative strategies will increase performance and productivity. Businesses will see it as a win-win, and I would say there is a lot of evidence building towards the direct cost being nil (easily measurable in terms of productivity), with indirect benefits related to engagement and retention proving quite appealing too (equally measurable)! "

Given the labour shortages which could persist as the baby boomers retire, is a four day week viable?

Charlotte Lockhart, Chief Executive Officer at 4 Day Week Global replied: "The 4 Day week is essentially a conversation about productivity in a business and how to improve it so you can spend less time there. While we will have baby boomers retiring, we will equally have more technology to replace workers and a workforce full of Millennials and the generations that follow them that actually want to work less. Therefore work is going to have to adapt to this new environment. The days are gone when we can take a lazy approach to a business problem by fixing it with a cheap and overworked labour solution. The benefits to business, workers, our society and our planet of working less make the changes necessary worth the effort.

Andrew Barnes, 4 Day Week Global Architect, said: "Organisations adopting the 4-day week generally see an increase in productivity compared to the traditional 5-day model. Producing more in less time then frees up employees to have more time available for care responsibilities (amongst other things) so arguably this becomes more appropriate and necessary as the baby boomers retire in increasing numbers.

Is technology the reason why we are considering a four day week now?

Charlotte Lockhart: "People are the reason we are considering it now. Even before the pandemic, we saw a ground swell of companies taking their employees' well-being' seriously. Now, post-pandemic, The Great Resignation is empowering our workforce to take the matter into their own hands. As a result, employers now have to find ways to engage with people to attract and retain the best staff.

Andrew Barnes: "Whilst technology has certainly been a part of the productivity revolution, changes to work patterns, the work environment and the reduction in busy-ness or non productive activities have a bigger impact."

Would a four day week mean people earn 20 per cent less? If not, how can employer's afford a four day week?

Charlotte Lockhart: "The programme is about increasing productivity in a business so time off can be rewarded. When you maintain productivity, there would be no reason for an employer to reduce pay. In fact, it would be wrong. So we are encouraging a shift from paying on time to valuing time."

With remote working, how can a four day week be viable?

Aren't we moving to an era when people work all kinds of hours anyway, and something as specific as a four day week doesn't fit this new way of doing things?

Charlotte Lockhart said: "We actually encourage businesses to find their own version of a reduced hours workplace. This might mean 32 hours over five days; it could be a whole day off, it might be two afternoons. In some companies/countries where the average workweek is more than 40 hours, India for example is 48; we encourage businesses to reduce to 40 hours before trying to get to 32."

Damien Stork said: "The absolute opposite, I would say. Presenteeism reflects disengagement, and disengagement is at record highs. This is due to several practical things and not just that Covid has caused many people to fully re-evaluate their lives and what they do. Disengagement is prevalent in poor mental health, so it makes sense to me that as mental ill-health rises, so does disengagement. Presenteeism is not related to a physical location; it is related to how well we are; a major factor is how engaged we feel in our work, colleagues, and company. "

Andrew Barnes said: "Working from home can also be described as 'sleeping in the office' and research has shown that working hours have encroached on rest time during the pandemic. The 4 day week is about reducing working hours. Where we work is irrelevant…how long we work, and overwork, has to be addressed regardless of location. Arguably reducing working hours by the 4 day week is more relevant than ever!"

The other side of the story takes quite a different view:

Recently, Mary Callahan Erdoes, the CEO of JP Morgan Chase's Asset and Wealth Management division, talked up the importance of young graduates working 72 hour weeks. She said this helped them learn their craft at a more rapid pace — getting the 10,000 hours experience they require to gain base level mastery within around two half years, versus five years if they work eight hour days.

What's the point?

But this all begs the question why? If we work 72 hours a week for a bank, are we doing either ourselves or society any good?

For some, work is what they enjoy. If you write for a living, then research can take up an excessive amount of hours, but it doesn't always feel like work.

We are all different. Enforcing shorter weeks might not be to everyone's liking. But neither do we want to continue in the 'long hour's arms race', in which people feel forced to work long hours due to poor human resource planning.

We are in the midst of the fourth industrial revolution. So if, as a result of technologies such as AI, RPA, robotics, 3D printing and automation in general, we don't end up working a few hours, aren't we entitled to ask: "What's the point of technology, then?"

Related News

The tyranny of rightwing snowflakes and far-right wokism

Mar 14, 2023

Unconscious bias 1930s Germany and the BBC

Mar 14, 2023

Microsoft CEO says AI can reduce inequality

Jan 24, 2023