Inflation is like a bungee jump, the risk lies with inflation expectations, technologies including automation provide the hope.

What has happened?

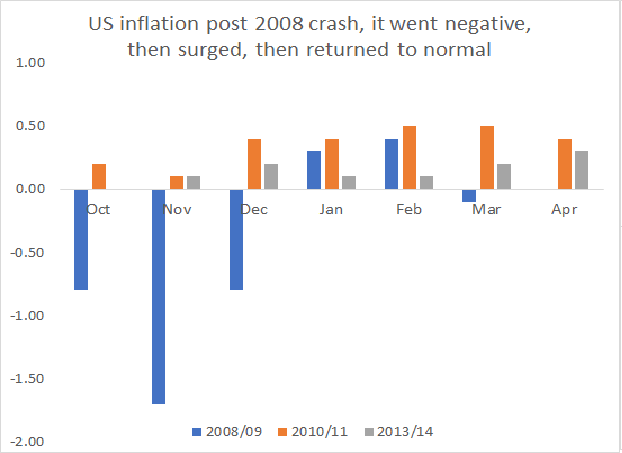

US inflation is at its highest level since 2008 — the annual rate in May was five per cent. It is just that comparisons with 2008 don’t really mean a lot. Until last year, the 2008 recession was the deepest economic downturn since World War Two. Post-2008, lots of scare stories did the rounds concerning inflation, but we can now say, with the full benefit of hindsight, that they were just that; scare stories, and which turned out to be wrong.

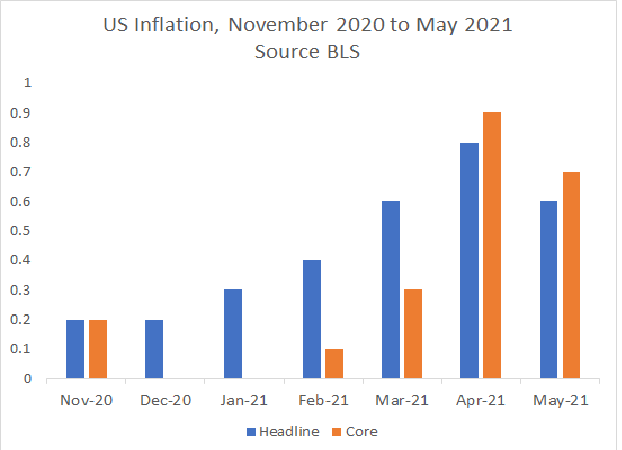

What is possibly more concerning is that the annual rate of US core inflation in May (excluding food and energy) rose to 3.8 per cent, the highest level since 1992.

But then again, take another look at the data. The month on month rate was actually lower in May than in April.

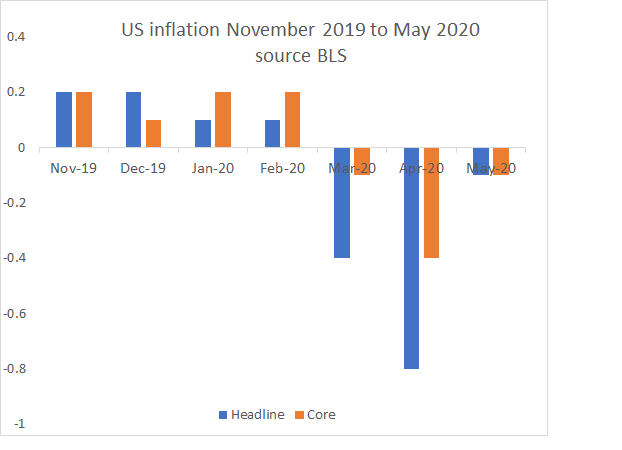

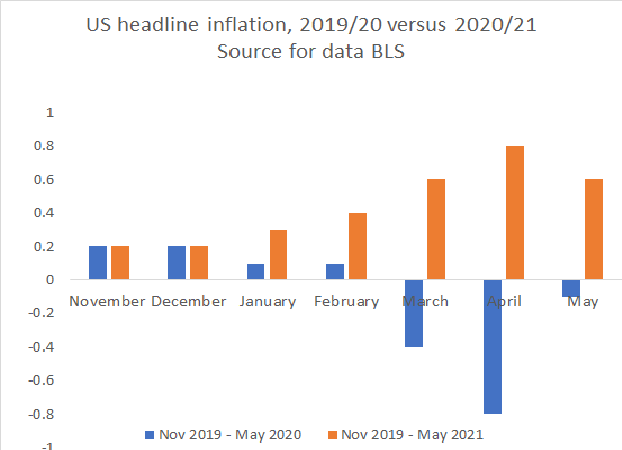

Inflation can follow the trajectory of a bungee jump, if falls, rises but then falls again. In April last year, US month on month inflation was minus 0.8 per cent. The annual rate was just 0.1 per cent. Price increases were inevitable, just to make up for last year’s price drops.

Labour supply

The concern is that we might see a shortage of labour — that lower-paid workers, in particular, seem to be in low supply; thus, their might wages go up. I say concern; some might argue this is a good thing, of course.

An article in the Economist included a rather apt comment. Referring to an interview with a pub owner, the article stated: “Asked if he might have to raise wages in order to attract a chef, the Peterborough pub owner pauses for a moment, before admitting “it might come to that.”

Asked if he might have to raise wages in order to attract a chef, the Peterborough pub owner pauses for a moment, before admitting “it might come to that.” https://t.co/Boc1Rv5ETs

— Duncan Weldon (@DuncanWeldon) June 10, 2021

In the UK, Brexit is having an impact as low paid migrants leave the country. There is also the more significant, demographic trend. The population is ageing — as it is in countries that were supplying the migrant labour. As the baby boomers retire, a labour shortage may well emerge, which throws a cloud of confusion over claims automation will destroy jobs. (This demographic shift is one of the great ironies of the immigration debate; immigration was going to fall and then go negative, anyway.)

Lesson of history

It might be worth recalling what happened in the 1970s. Back then, as OPEC became more assertive, the oil price went up, leading to broader price rises. Unions reacted by demanding higher wages for workers. Higher wages meant employers had to increase prices. At the same time, higher wages led to higher demand, but output didn’t rise; thus, inflation rose again, and unions demanded even higher wage increases.

But it was what happened next that provides the real warning. Unions noticed that inflation was ongoing. So, not only did they demand higher wages to cover existing increases in the cost of living, they began to demand higher wages in anticipation of higher inflation. At this point, we saw an upwards inflation spiral that threatened to run out of control. The governments of that time tried to counteract rising inflation with wage freezes, leading to massive clashes between unions and employers.

The then UK Prime Minister, James Callaghan, said: “We used to think that you could spend your way out of a recession and increase employment by cutting taxes and boosting government spending. I tell you in all candour that that option no longer exists, and in so far as it ever did exist, it only worked on each occasion since the war by injecting a bigger dose of inflation into the economy, followed by a higher level of unemployment as the next step.“

Might we see a repeat?

One big difference today is that unions have much less influence. Another difference today is that we have gone through a period in which productivity growth has outstripped wage growth. Between 1979 and 2019, US hourly pay increased by 17.2 per cent, while US output per hour work grew by 72.2 per cent. The data might suggest there is plenty of scope to increase pay.

The bungee jump

There is one big unknown; what will happen next? As the Economist writer Duncan Weldon Tweeted: “Lower waged workers are in demand at the moment. And they might even have a bit of pricing power in the jobs market.

But - they had an awful 2020; a lot of this is catch up. And this shift in power might not last.”

Short version of this week’s piece: Lower waged workers are in demand at the moment. And they might even have a bit of pricing power in the jobs market.

— Duncan Weldon (@DuncanWeldon) June 10, 2021

But - they had an awful 2020, a lot of this is catch up.

And this shift in power might not last.

Returning to the data, yes, core inflation rose by 0.7 per cent in May, but one of the big factors that drove up prices was used cars and trucks. Energy prices were up too. But these increases were probably one-offs, largely counteracting last year’s falls.

So, inflation may well follow the trajectory of the bungee jump. Last year it plummeted, this year, it bounced back; next year, or maybe 2023, it should fall again.

Meanwhile, Jeroen Blockland has speculated on whether the oil price might return to $100 a barrel. If it did, that would be three times the level seen during the depths of the Covid crisis but also double the level seen throughout much the five years before Covid. But remember, the oil price surged past $100 a couple of years after the 2008 crash, before falling back,

Is #oil going to USD 100?https://t.co/tnib9OsdhE

— jeroen blokland (@jsblokland) June 9, 2021

ht @LizAnnSonders

If you wish to receive the Daily Insight by mail, please sign up here https://t.co/47UkUxDLoC pic.twitter.com/x4rjOTcmcM

Technology

But the difference between today and the 1970s is technology

In the 1970s, energy output was dependent on oil and coal; today, renewables and energy storage are key, and energy from renewable energy is on a downwards trajectory.

Sure the cost of second-hand cars and trucks went up in May, but within three to four years, the entire car market and truck market, both first and second hand, will be disrupted by electric vehicles, creating lower costs.

Sure, there could be pressure from the labour market caused by demographic changes, but automation hasn’t gone away.

Automation technologies will lead to higher output per hour worked.

Then there is remote work — this will be a deflationary force because it will take fewer inputs to create the same level of output as before; for example, spending on travel will decrease, as will spending on office space.

Expectations versus technology

This is not to say there is no risk of sustained inflation; if we all start to anticipate inflation, that could spark off an upwards spiral. But technology is likely to mitigate against this.

We won’t know the answer for a while. We won’t know until mid-decade, but to be clear, the Techopian view is for the economy to perform exceptionally well this decade, while inflation is modest, averaging somewhere between two and three per cent a year.

Related News

Liz's poisoned chalice and the hint of hope

Sep 06, 2022

Cut profits to pay workers: does it make sense?

Jul 05, 2022

Is rationing the solution to the cost of living crisis?

May 30, 2022